Going Dutch – what can the UK learn from the Netherlands approach to cycling?

Global design and consultancy Arcadis, with its roots in the Netherlands, has been leading active travel solutions for decades. With the pandemic necessitating a renewed focus on active travel in the UK, what can we learn from the Dutch experience?

Following the joint ADEPT/Arcadis webinar this month, Arcadis’s Keri Stewart, Technical Director in the UK, and Marloes Scholman, Project Leader in the Netherlands, share their thoughts.

A nation of cyclists?

From the outside, the Dutch are perceived as a nation of cyclists but that has not always been the case, and nor is it how they see themselves. The Netherlands had its love affair with the car, but since the 1970s, the approach to transport has taken a very different path from the UK.

Through the 1950s to1970s, Dutch transport systems were redesigned to reflect the growing dominance of the affordable car. However, concern for rising death rates led to public demand for safer roads and a subsequent change of policy focused on ‘liveable streets’ - the belief that urban areas are meant for living, not transport.

Over time, this developed into a clear categorisation system for roads - access, flow and residential - to determine priority and then design. The first national strategy on cycling was introduced in 1989, and since then, the development of a high density cycle network has made everything accessible for bikes. There are now 35,000km of dedicated cycle paths and bike parks, and cycling between small cities is common with easy connections to big cities. Junctions and roundabouts can include tunnels or different routes for bikes and there is no route sharing with pedestrians.

The key factor in the design process for liveable streets was to concentrate on neighbourhoods – making the daily school run and local shopping safe and easy for families. This approach extended to the supporting infrastructure, with well-funded maintenance, and room to park bikes in front of schools, shops and at work, all factored into a whole system approach. Up to seven bikes can be parked in one car space and guarded parking, for example outside train stations, is free for the first 24 hours. Employers often offer benefits for cycling and offer shower facilities on the premises.

As a result of this policy and the reorienting and categorisation of Dutch streets, the number of cyclists has grown over the past 30 years and now daily cycling is an everyday part of Dutch living. Normal clothes are worn, with lycra and specialist bikes reserved for sports use. It’s not unusual for people to have different bikes for different purposes, whether that’s carrying small children and shopping, or for longer journeys. Children learn to cycle from the ages of two or three and later, cycle with their parents to primary schools. With no school buses in the Netherlands, they never lose the habit, moving on to cycling on their own and later, to secondary schools.

Cycling in the UK

In contrast, the UK approach has been very different, resulting in fragmentation. The car has remained the dominant mode of transport and as a result, supporting infrastructure has encouraged and enabled car dependency. This means that de-trafficking a neighbourhood has become contentious and politically charged, despite communities wanting to improve the quality of life in their areas. There can be a lot of negative push-back, which is taken up by local media, with an emphasis on the car being integral to personal freedom. Importantly, there are not enough segregated cycle routes for people to feel safe, so take-up on the school run, for example, is low. Schemes like the Manchester Cyclops remain the exception.

Funding is also a factor in this fragmented approach. Mechanisms like WEBTAG, are focused on financial monitoring, so that value for money and return on investment rather than the broader, but equally important benefits of health and wellbeing, reduced congestion and improved air quality inform investment decisions.

Separate schemes mean we too often see disappearing cycle lanes that stop and start abruptly, rather than building an integrated network that encourages active travel. In addition, funding for ongoing maintenance is subject to a prioritisation hierarchy which has also favoured the car. This has sometimes meant that where cycling routes have been put in place, there has not been the funding to adequately maintain them – again illustrating the lack of a national strategy in the UK.

How can the UK move forward?

It’s not a case of just copying and pasting the Dutch experience. The UK needs to move forward faster, but one thing that can be learnt is to start with dreaming big. If you understand what you would like your neighbourhoods to be, you start to look at towns and cities through a different lens. Examine the role of each street and begin decision-making based on those functions. Look at different routes and understand the point of them. Look at how to make schools and shops accessible. The advent of COVID-19 has compelled placeshapers to rethink how our areas work. The 20 minute neighbourhood concept is gaining more traction with more people working from home and likely to remain doing so for at least part of their working week. How can we reshape our transport networks to reflect these changing needs?

Engaging with communities from the outset is critical. If residents buy-in to the vision from the start, each development and change is understood as part of an overarching plan. Behaviour change starts with winning hearts and minds, so celebrate success. Positive messages on safety and health benefits encourage behaviour change, and rather than castigating people who continue to rely on cars, make it easy for them to switch through a whole package approach. E-bikes and e-scooters also have a role and although they were initially adopted by older people in the Netherlands, they are now used increasingly for longer distances. A focus on local areas, ensures schools, shops, hospitals and employment areas have the supporting infrastructure built-in.

The UK can learn about standards and what works from the Dutch experience, but it’s not only for local authorities to address. Nationally, we need an overarching strategy and funding that doesn’t just enable new routes, but also considers the wider supporting infrastructure, planning and ongoing maintenance. That is also an intrinsic part of the Dutch approach.

To break this down into key actions, we need to:

- Start with a clear vision for liveable places with provision for increasing cycling

- Communicate with communities from the outset, emphasising the benefits and warm people up to new routes so people know what’s coming

- Secure political buy-in and adopt cycling ambassadors to support and encourage take-up

- Create safe & reliable main routes to destinations - not detours

- Build the supporting infrastructure – safe parking spaces, rentals and lending stations - and provide adequate funding for ongoing maintenance

- Take small steps - build positive experiences for daily cycling

- Stimulate specific target groups – eg students and enable schoolchildren to cycle safely from a young age

- Celebrate success and each improvement – even minor ones.

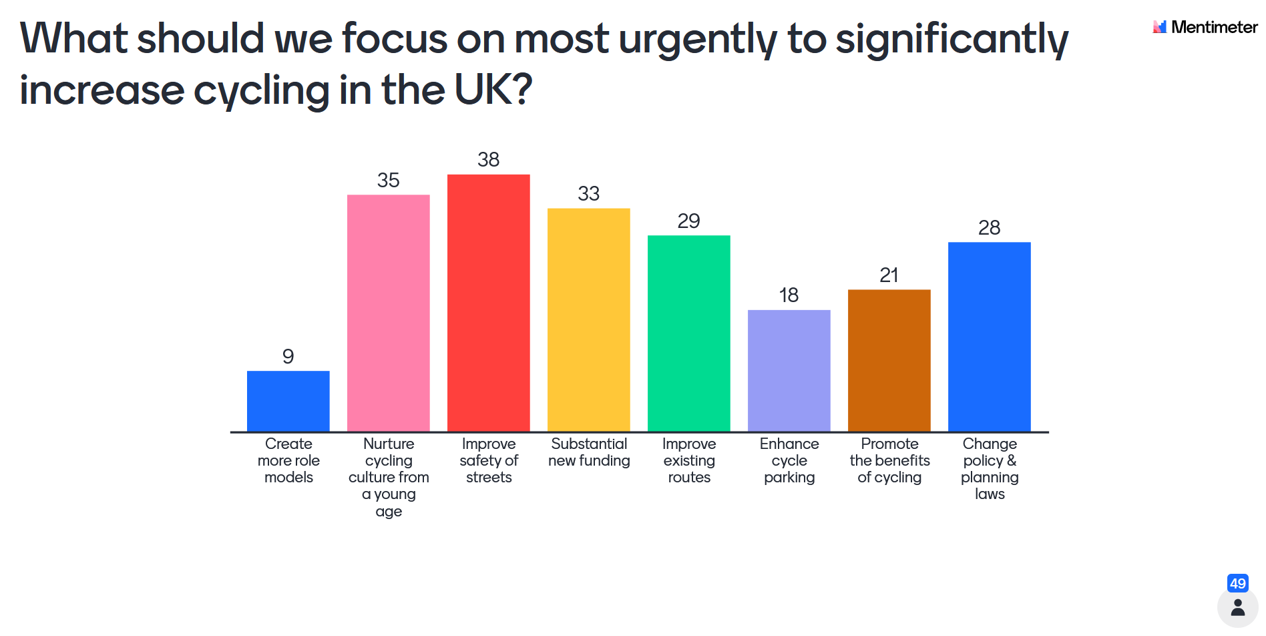

During the webinar, we conducted a survey on how we can better support cycling take up in the UK, the responses prioritised safety, nurturing a cycling culture and a significant funding increase.

ADEPT’s Active Travel Policy is available here: https://www.adeptnet.org.uk/documents/adept-policy-position-active-travel

For more information on the Dutch experience, visit: https://www.dutchcycling.nl/en/ or here for the latest Arcadis white paper and podcast.